![]()

When dealing with the interpretation of music from the past, we must never forget how different the performance techniques have been over the centuries. As in every art – in painting, in sculpture, in the science of building – performance technique has also undergone many changes over the centuries in music.

The evolution has originated both from changes in musical aesthetics and from innovations in the construction of musical instruments. It is necessary, however, to abandon the prejudice that ancient techniques are primitive. Instead, we must look for the logic that unites compositional style, musical aesthetics, performance technique and instrument construction: suddenly the meaning of certain fingerings handed down to us from ancient sources and completely different from those in use today will appear.

In a series of short articles, I will attempt to introduce the fingerings used in specific historical moments, explaining their meaning and contextualising them in the musical aesthetics of the period.

Sources

The oldest source that tells us about fingering dates back to 1462 and is preserved in the Prague Castle Archive. In some music sheets, after some melodic formulas, the ‘dispositione digitorum‘ is indicated, i.e. with which fingers to perform the notes of these simple figures. In each hand, only the index, middle and ring fingers are used!

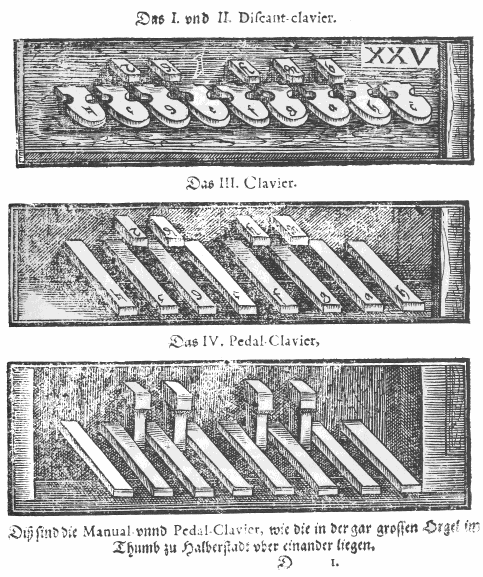

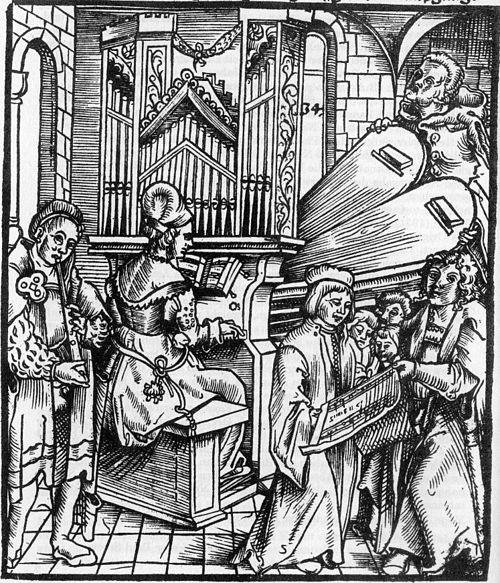

At the end of the Middle Ages, the organ often had keys that were moved more by the fist than by the fingers (see the illustration below, found in the treatise Syntagma musicum by Michael Praetorius). The strongest fingers, the middle fingers of the hand indicated by the Prague manuscript, represent the next step after playing with the fist. Playing with the fist is a tradition that has survived in the carillon players of the bell towers of northern Europe.

Between the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century, a refined organ culture developed in southern Germany and along the northern arc of the Alps. There is much evidence of this art: the Buxheimer Orgelbuch, the music of Conrad Paumann, Arnolt Schlick, Paul Hofhaimer and his many pupils.

But how was this music performed? We find some answers in Arnolt Schlick’s treatise, Spiegel der Orgelmacher und Organisten (1511) but above all in Hans Buchner’s Fundamentum, a manuscript preserved at the University of Basel.

The Fundamentum of Hans Buchner

Hans Buchner, also known as Hans von Constanz (Ravensburg, 26 October 1483 – Constance or Überlingen?, 1538), belonged to a family of organists and organ builders. He studied music with Paul Hofhaimer, with whom he lived for about two to three years. He was organist to the imperial court, replacing his master, who held the post, while the latter worked in Passau. Appointed then to the cathedral in Constance, from 1506 he was also organist in Basel, obtaining a life tenure from 1512. From 1526, he moved to Überlingen, due to the Protestant Reformation that had reached Constance. He spent the following years in relative poverty. His pupils included his son Hans Konrad Buchner and Fridolin Sicher, organist of the collegiate church in St. Gallen. Much of his music is linked to the liturgy and thus to the practice of alternatim with Gregorian chant, but there is no lack of secular compositions.

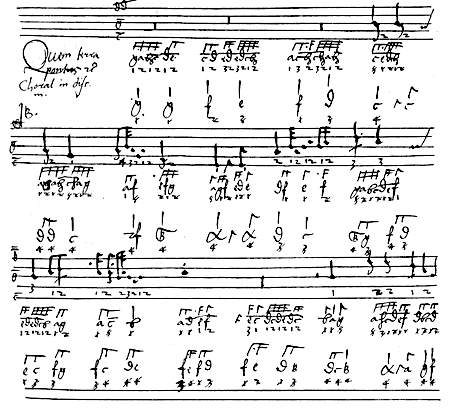

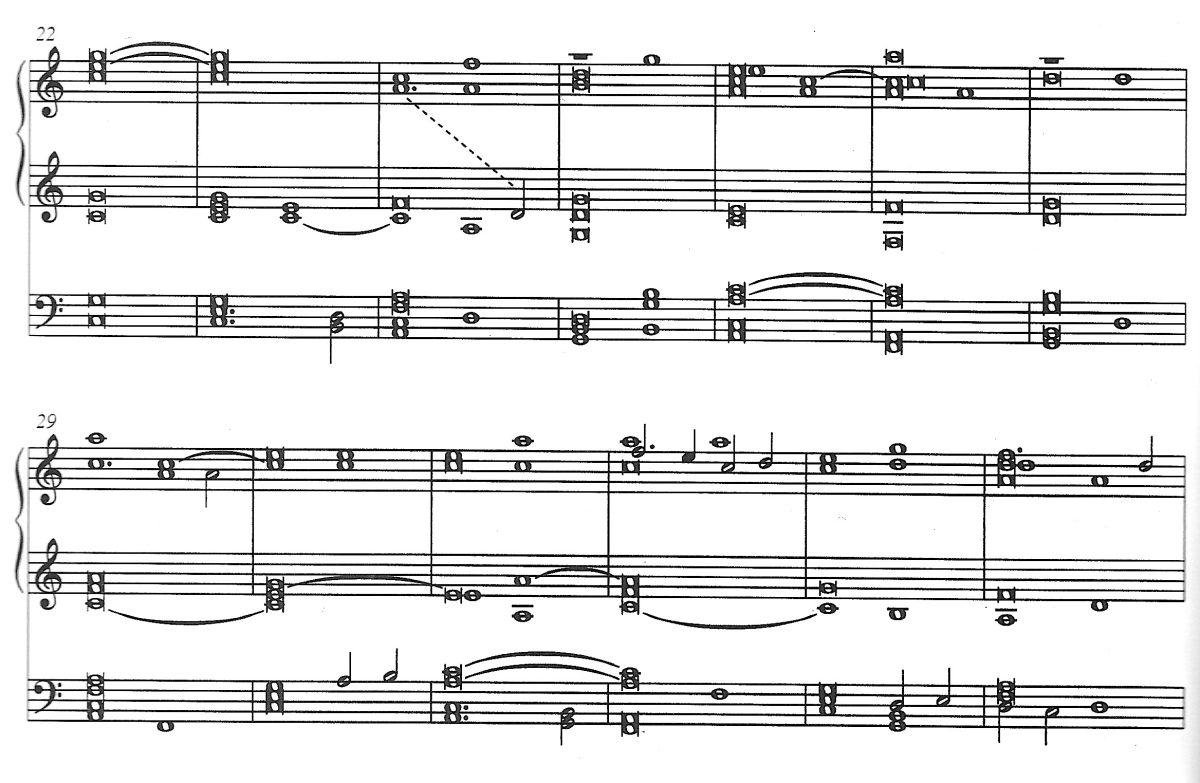

Buchner’s teaching on the use of fingers is a veritable window opened on the performance style of the past. He gives us a precise set of rules for the execution of fast figurations and for intervals; at the conclusion of his rules Buchner encloses, as an example, a three-voice composition entirely fingered. This is an elaboration of the Gregorian hymn Quem terra pontus, with the Cantus firmus in the upper voice.

The original source uses old German alphabetical notation (the upper voice in mensural notation, the other two voices in alphabetical notation):

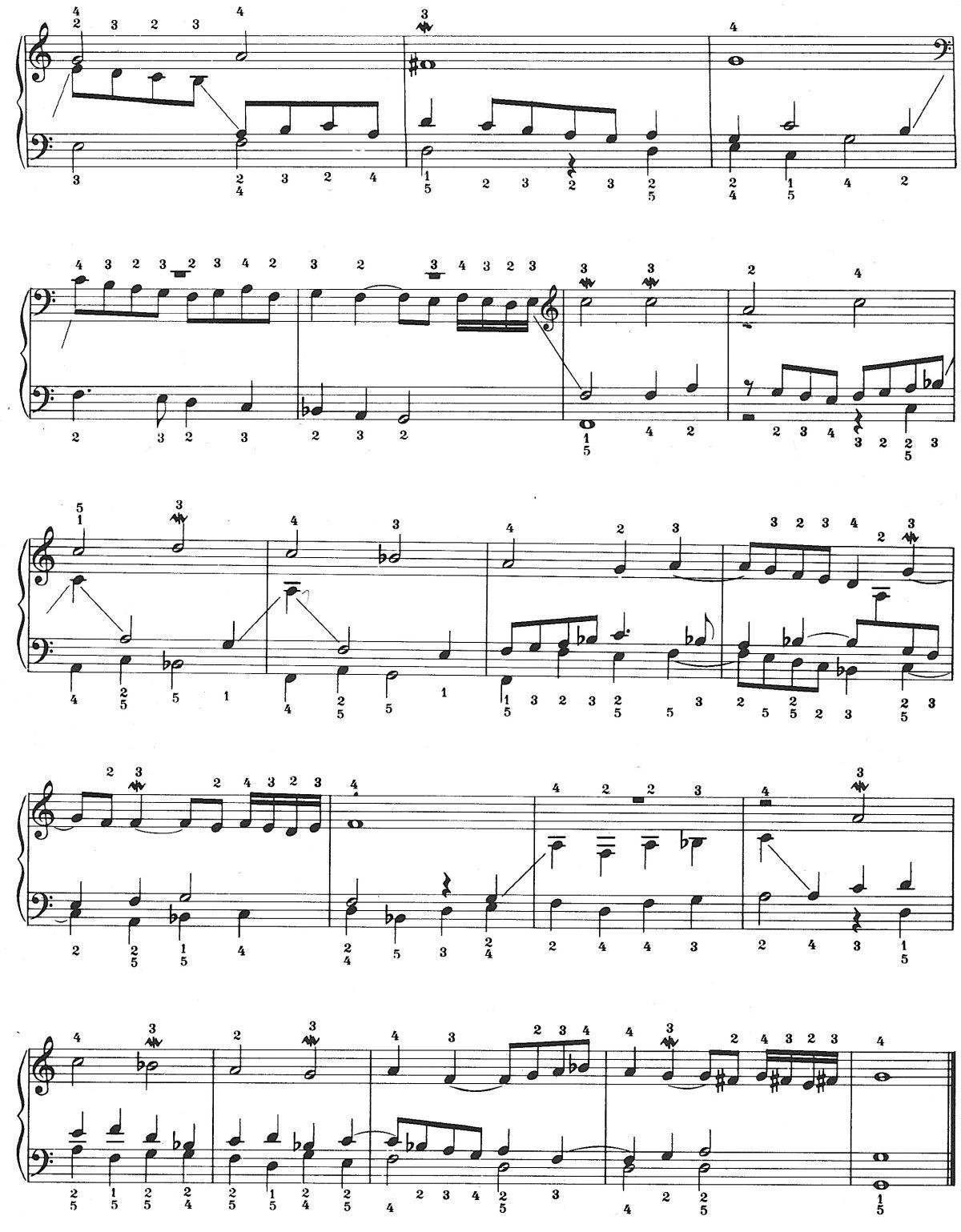

Here the modern transcription:

If we try to perform this piece with the author’s fingering, we notice a few rules:

the intervals played simultaneously by one hand are: Thirds (played with second and fourth fingers); Fifths and Sixths (with second and fifth fingers); Octaves (with first and fifth fingers). The execution of two voices with the same hand and the respective fingerings are rules 6, 7 and 8 of the Fundamentum; these rules are strictly applied throughout the piece.

The ornamental diminutions are not, as would be the case later in the Renaissance, long successions of fast notes but are limited to groups of four notes, executed in a very articulate manner (as is clear from the fingering of the figure in bar 8).

The fastest notes are played alternating the second finger and the third finger, with the second finger falling in the accented metric value. When one hand has to play two voices at the same time, the moving voice takes precedence and long notes are held far less than their value: sometimes they are just touched and immediately abandoned. See for example the left hand at bar 5.

If we play with the assumption that we hold the notes for their full value, when this is possible, the result is a great unevenness of the melodic lines: sometimes we can hold the notes for their full value, sometimes we are forced to shorten them greatly. In my opinion, voices only become linear if the notes are always played relatively short, even when it would be possible to hold them to the end of their value!

By playing in this way, the result is a peculiar sound image that has a complete musical sense, similar to the performance of a lute player rather than what for us is the typical organ performance, with long, held notes; the most valuable notes are in fact not defined in their duration and make room for the small notes that move. It is then our mind that reconstructs the linearity of the voices.

But wasn’t such separate playing perceived as too broken?

I think not, especially in light of three considerations:

- In the 15th and 16th centuries, the great Gothic architectures, where the instruments were placed, were rooms with a long resonance where it was necessary to separate the sounds and pronounce each note well.

- Almost all organists of the time were also lutenists. Arnolt Schlick’s 1511 collection is, for example, entitled Tabulaturen etlicher lobgesang und lidlein uff die orgeln un lauten (Tabulations of various hymns and songs for organs and lutes). See also how Hans Buchner indicates the execution of the mordente: the second and third fingers strike the keys together and while the third finger holds the note, the second finger – tremebundus more – quickly strikes the lower note; an ornamentation also attested to in the Spanish treatise Arte de tener Fantasia (1565), by Tomas de Santa Maria. An apparently very strange ornamentation, but one that imatates the technical gesture that lutenists use to perform a trill: two fingers strike the keys together but only one moves quickly.

- The last consideration is about the organs of the time: the keyboards had very large keys, where it could be difficult to reach an octave with the same hand (see Arnolt Schlick’s treatise, Spiegel der Orgelmacher und Organisten); the bellows and wind system was relatively primitive and playing too tightly would have emphasised the very unstable ‘wind’ (see the two bellows feeding the organ that adorn the frontispiece of Schlick’s print).

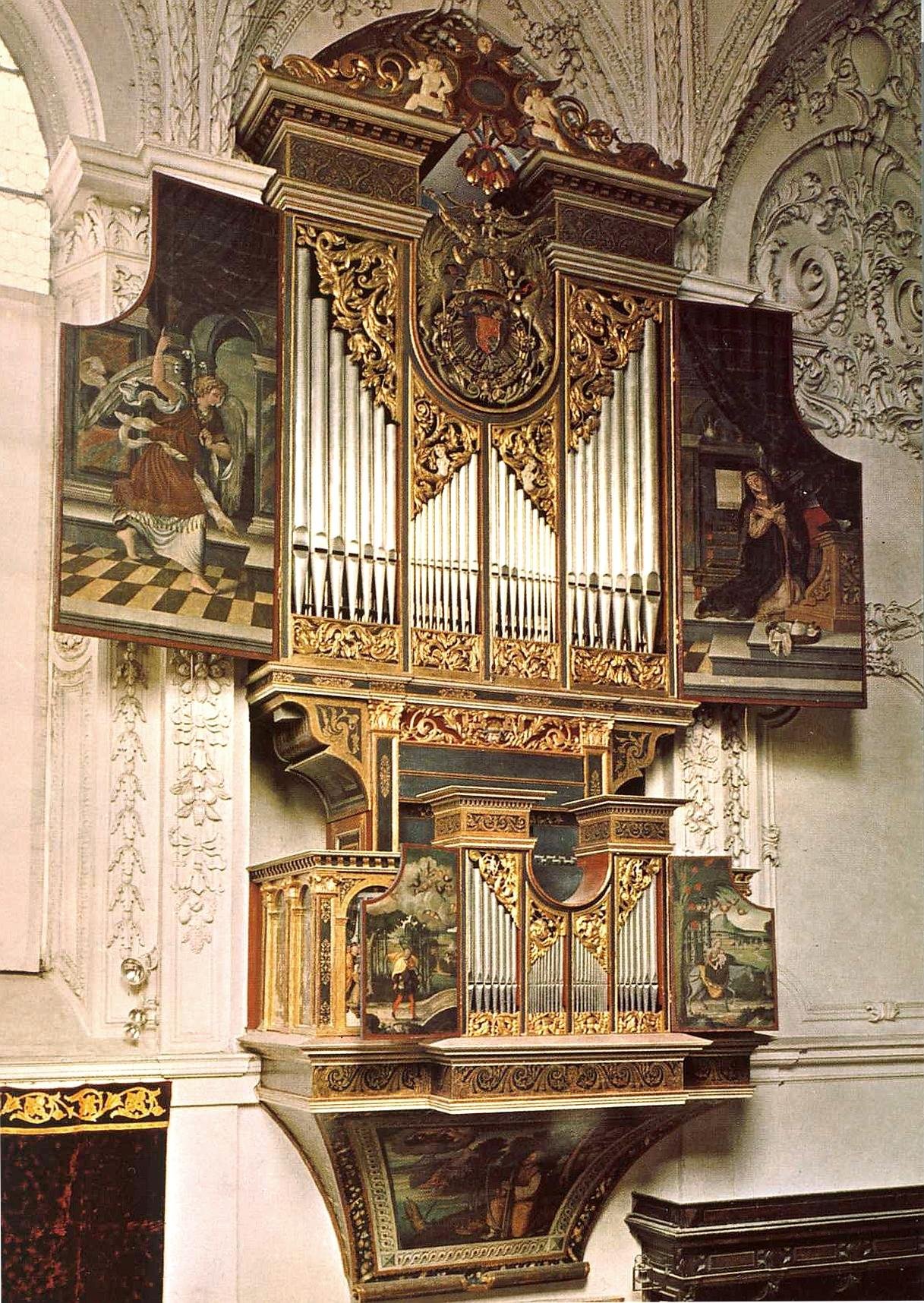

At the same time, the intense and flamboyant sonorities lent themselves well to clear and paced playing. The still existing organs of Rysum and the Innsbruck Court Church give us a picture of these instruments.

Ebert Organ (1555) of the Court Church in Innsbruck

In the light of Buchner’s Fundamentum, we can better interpret Arnolt Schlick’s instruction to perform his composition Ascendo ad Patrem meum a 10 voices, with four voices at the pedal. In this musical page, too, each chord was actually simply struck; there was certainly no idea of connecting one note to the next, but rather there was a wide silence of articulation between each chord. Only in this way does performance become possible!

Unfortunately, we do not have much information on 15th- and early 16th-century organ music in the rest of Europe. Buchner’s playing technique probably had points in common with the technique of other geographical areas. Pronounced articulation is well suited to the compositions of the Buxheimer Orgelbuch; perhaps the music of composers such as Marcantonio Cavazzoni or John Redford was also played with a very loose stance on the keyboard and with wide articulation silences.

The alternation of the second and third finger would remain for a long time, as an archaic trait, even in later schools (e.g. this fingering is indicated for left hand scales in the treatise Il Transilvano by Girolamo Diruta, Venice 1593)….. but we will discuss this when dealing with Renaissance fingerings.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q204iMC4ndc